Cocaine’s History in America: Was it Ever Legal?

Cocaine and its addictive influence stand as such powerful points of reference in American culture that when a 2013 study suggested that Oreo cookies were as addictive as cocaine, the findings made “thousands of headlines.” 1, 2 Such claims are just another addition to the long, turbulent, and scandalous history of cocaine in America.

Why is cocaine illegal? This article will explore the history of cocaine and its place in the American landscape — and how its potent addictive properties and reputation worked to change cocaine’s legal status to a Schedule II drug.

Where Cocaine Came From

Cocaine comes from the coca plant, a plant native to the jungles of Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and neighboring countries. Historically, people in these regions would chew the leaves of the plants in the coca family, partly for its nutritional value, but also because consuming the leaves would impart stimulant and analgesic effects. Such a custom provides the first glimpse into how cocaine became a household name across the world.

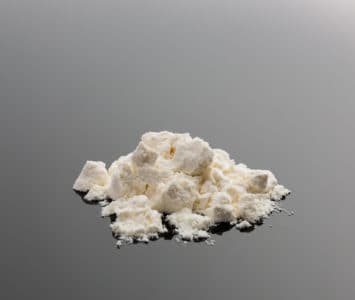

In Drugged: The Science and Culture Behind Psychotropic Drugs, author Richard J. Miller posits that European (primarily Spanish) explorers and colonists observed how the natives they conquered were rarely without the coca leaf in their mouths and, as a result, adopted the habit themselves.3 Word about how the coca leaves helped indigenous peoples stave off exhaustion and hunger made its way across the ocean to Europe, where the scientists of the early 19th century eventually extracted pure cocaine as a white, crystalline substance. A historian writes that this more concentrated cocaine extract was “tens to hundreds of times more powerful” than simply munching down on the coca leaf.

Original Uses for Cocaine: Medication and Treatment

The primary psychoactive compound in the coca plant is cocaine; however, the cocaine content in the raw leaves is very low, below 1 percent. Chewing the leaves, grinding them into powder, and mixing them into tea, is unlikely to produce the infamous euphoria, or lead to potentially devastating physical and mental damage, as is the case when cocaine is injected or snorted.

The numbing properties of cocaine caught the attention of an Austrian ophthalmologist, whose use of the substance as an anesthetic for eye surgery was met with success and praise across Europe. Prior to his intervention, eye surgery was considered all but impossible because of the minute and reflexive motions of the eyeball to the slightest stimuli. Cocaine as an anesthetic allowed a doctor fuller range of operation, piquing the interest of doctors of various fields (such as dentistry).

As cocaine’s medicinal fame spread, its recreational effects did not go unnoticed. A French chemist combined wine and cocaine to produce Vin Mariani. There were 6 milligrams of cocaine in each ounce and a full bottle of Vin Mariani contained around 200 milligrams of cocaine. Believing that the drink could improve health and vitality, as well as boost energy, the concoction was endorsed by high profile figures such as Thomas Edison, Ulysses S. Grant, and two popes.

How Cocaine Reached America

Two Americans took note of the European cocaine craze. One was a surgical pioneer by the name of William Stewart Halsted. Halsted, too, was taken with the idea of using cocaine as a painkiller and set about experimenting with the drug—on himself, his colleagues, and his friends. Even as Halsted’s use devastated his physical and mental health he was unable to control his addiction. Despite these reported effects, cocaine enjoyed such a wave of popularity in the United States that the negative effects of the drug were largely ignored or buried.4

One man who cashed in on cocaine’s public appeal was John Pemberton, who was inspired by the commercial success of Vin Mariani and decided to try his own hand at creating a cocaine-based drink in the United States. Wounded in the Civil War and addicted to morphine, Pemberton attempted using cocaine as a form of treatment. One attempt utilized his knowledge of pharmacy to develop what he called “Pemberton’s French Wine Coca,” which he marketed as a cure-all for any number of ailments and even as an aphrodisiac.5

However, Pemberton’s home state of Georgia enacted temperance legislation in 1885, outlawing the sale of alcohol. With his French Wine Coca now barred from actually having any wine in it, Pemberton replaced the wine with sugar and marketed the new product that would eventually be trademarked and known as Coca-Cola.6

What Was Cocaine Made Illegal in the United States?

The effect that cocaine had on William Halsted, whom The New York Times calls both the founder of modern American surgery and a lifelong drug addict, heralded the end of the cocaine honeymoon.7 As cases of devastating addiction and mental health damage started to be connected to cocaine use, the drug fell out of favor with a once-enraptured American public. Sigmund Freud, who publicly advocated cocaine’s effectiveness in treating anxiety and depression, was similarly “nearly destroyed” by his use of the drug, and in the words of PBS’s Newshour, recanted his support of cocaine after he experienced frequent nosebleeds and irregular heartbeats.8, 9

Around this time, Congress began debates about whether to pass the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act. Unprecedented for its time, the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act set out to regulate and tax the importation, manufacturing, and distribution of opiates and coca products, in part to mend relations with China by clamping down on the illicit opium trade. While some states saw the act as the federal government trying to involve itself in states’ rights, the tipping point came with newspapers, politicians, and even physicians stoking the fears of the “cocaine fiend.” This fear fueled passage of the law and the Harrison Act became law — one of the first pieces of American legislation on the issue of drug regulation.10

After the passage of the act in 1914, heralding its illegal status, cocaine remained largely dormant in the American psyche. Cocaine was mostly forgotten as one generation passed, and another took its place.

Why Is Cocaine Illegal?

Cocaine is considered a Schedule II narcotic by the DEA, which means it has a high potential for abuse (though it has some limited medical uses). The move to make cocaine illegal is rooted in mixed and complicated history of concern for public health and safety, politics, and racism.

Illegal use of Cocaine in the U.S.

But a substance as potent as cocaine never truly goes away. When the hippie movement of the 1960s started experimenting with mind-altering substances to fit the music and zeitgeist of the times, their first drug of choice was the relatively harmless marijuana.11 As the movement expanded, stronger drugs were brought in, such as the psychotropic LSD, DMT, and psilocybin.12

By the middle of the 1970s, the hippie movement was on the way out, but its impact had been made. By then the rich and trendy adopted cocaine as their own, regardless of its illegal status. Indeed, such was the popularity and attraction of cocaine that there were even print ads for cocaine paraphernalia.14

Cocaine in the 70s and 80s

Cocaine’s return to prominence at the end of the 1970s set the stage for the era of “sex, drugs and rock and roll” in the 1980s. Rolling Stone magazine profiled the decade as being one of “extreme” sexual activity, drug use and, of course, rock music. A survey conducted by the magazine found that 20 percent of respondents admitted to trying cocaine.13

The decade also benefitted from what The New York Times referred to as “the greatest, [most] consistent burst of economic activity” the world had ever seen. From 1982 to 1989, there was the creation of 18.7 million new jobs, with $30 trillion worth of goods and services produced. A generation of young, ambitious men and women had a lot of money to burn.15 The era was infamously portrayed in the 2013 movie The Wolf of Wall Street, set in 1987.

Crack Cocaine in the U.S.

But cocaine couldn’t keep up with the rabid demand among the social elite. Towards the end of the 1980s, cocaine manufacturers began to cut cocaine with other substances such as baking soda, in order to dilute the pure drug. This made it cheaper to make and buy — and more available to anyone.

Creating this form of cocaine entails heating it until it produces a cracking sound, giving it its name: crack cocaine, freebase cocaine, or simply “crack.”16

When it hit the market, crack cocaine caught on in a big way. The Primary Care journal writes that hospitalizations for medical emergencies as a result of using crack cocaine increased by over 100 percent from 1985 to 1986, the time period in which inner cities and gangs started to distribute it.17 According to Gallup, cocaine abuse had gone from a celebrity problem into a “truly terrifying issue.” Gang warfare and the notion of “crack babies” (children exposed to crack cocaine as fetuses, causing premature birth and other infant developmental problems) led to 42% of Americans claiming that crack (and other forms of cocaine) was the “most serious problem for (American) society,” even though, says Gallup, there are far more alcoholics than crack cocaine addicts.18

There is a significant difference in how crack cocaine is perceived (vs. pure cocaine) in the United States, and how its use, possession, and distribution are punished by law enforcement. Numerous studies and examinations have shown that people arrested for crack cocaine-related reasons are given much more punitive charges than people who are arrested for charges related to the possession, use, or distribution of pure cocaine.

Laws and Regulations Around Cocaine

To illustrate this, the Washington Post uses the metric of mandatory minimum sentencing to highlight the disparity. A mandatory minimum jail term of five years would have been given to someone charged with possessing 5 grams of crack cocaine. On the other hand, a person would need to have 500 grams of pure cocaine to receive the same jail term. In other words, the threshold for minimum mandatory sentencing for pure cocaine is literally 100 times that of crack cocaine.19

One might assume that crack cocaine is more potent, more volatile than its powdered counterpart, thus justifying why smaller amounts of crack receive the same punishments as larger amount of pure cocaine. The truth, however, is that there is no significant difference in the potential for addiction between crack cocaine and powdered cocaine and both are just as illegal. As US News & World Report explains, the difference is not in the chemistry or addictive potential of crack cocaine; rather, the difference is found in who uses crack cocaine (and who was punished for using it), and that answer is largely determined by race.20

The Post quotes a 2009 report by Human Rights Watch that points out that Black Americans are three times more likely than white Americans to be arrested for drug possession, even though the difference between which racial groups use which drugs is minimal, at best.21

Cocaine Sentencing Disparities

The United States Sentencing Commission says that no other drug has the same number of racially skewed offenses as crack cocaine. In 2009, of the 5,669 crack cocaine offenders who were sentenced:

- 79 percent were Black.

- 10 percent were white.

- 10 percent were Hispanic.

When it came to pure cocaine:

- 28 percent were Black.

- 17 percent were white.

- 53 percent were Hispanic.

Perhaps the most damning statistic of the mandatory minimum sentencing disparity is that people convicted of powdered cocaine-related charges spent an average of 87 months behind bars; on the other hand, people convicted of offenses related to crack cocaine were incarcerated for 115 months.

In writing about the law separating crack cocaine and powdered cocaine sentencing was closed, the Los Angeles Times says that the difference between the two was never rooted in science (the way a law might have lesser punishments for marijuana- vs. heroin-related offenses). Instead, the difference came down to how crack cocaine users were perceived by the American legal system, the media, and the general public. Since crack is easier for low-income people to obtain, says the Times, and since low-income people cannot afford high-quality legal teams and rehabilitation facilities, low-income offenders are prosecuted much more harshly and regularly than richer (potentially white) offenders who don’t bother with crack cocaine.22

The Fair Sentencing Act

Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois pointed out that the uneven balance of the mandatory minimum sentencing practices between crack cocaine and pure cocaine have led to Black Americans being imprisoned six times more than white Americans for the same illegal use.22

The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, authored by Durbin, was signed into law by President Barack Obama to reduce the disparity between how much crack cocaine and how much powdered cocaine would be needed for federal criminal penalties to come into effect. From a 100:1 weight ratio, the difference was whittled down to an 18:1 weight ratio.23,24

In supporting the passage of the Fair Sentencing Act, the American Civil Liberties Union argued that the previous system of mandatory minimum sentencing for crack cocaine offenses targeted Black Americans, causing “vast racial disparities” in the length of prison sentences for similar crimes. Black Americans, says the ACLU, served an equal amount of time in prison for nonviolent legal offenses, as white Americans did for violent offenses. The ACLU writes that the Fair Sentencing Act reduces not just the legal imbalance between sentencing for crack cocaine and powdered cocaine offenses, but also the racial imbalances created by a “draconian” system that turned people of color against the American justice system.

Even beyond that, the U.S. Sentencing Commission voted to retroactively extend the new Fair Sentencing Act guidelines to people sentenced to prison for disparate crack cocaine offenses, even before the date of the law’s enactment (August 3rd, 2010). As a result of that, 12,000 people (of whom 85 percent are Black Americans) can have their sentences for crack cocaine offenses reviewed by a federal judge, with the possibility of those sentences being reduced by the terms of the Fair Sentencing Act.

The U.S. Sentencing Commission approved an amendment to the Fair Sentencing Act, increasing the amount of crack cocaine that would be necessary to trigger the five-year mandatory minimum sentence; instead of 5 grams of possession, a person would now have to be caught with 28 grams.25

Cocaine in America Today

The passage of the Fair Sentencing Act was a major step forward in the history of cocaine in America; but in a similar way that cocaine roared back into prominence in the latter half of the 20th century, even a milestone like the Fair Sentencing Act has only made a dent in cocaine’s presence in the United States. By the time the notorious drug lord Joaquin Guzman, head of the Sinaloa Cartel, was arrested by Mexican authorities in 2016, it was estimated that he and his organization had distributed more than 500 tons of cocaine throughout the United States since the late 1980s.26

Furthermore, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s 2011 World Report put the global value of cocaine at $85 billion in 2009, of which $38 billion came from the United States alone.27 The CIA World Factbook states that the United States is the leading cocaine-consuming country in the world, with South American countries (in particular, Peru and Columbia) smuggling their product through Mexico and into the US.28,29

Cocaine remains the second most popular drug in the world (behind marijuana), despite attempts by various South American governments to reclaim coca-producing territory from cartels, and regardless of its clear illegality in most countries.30 In 2016, the National Institute on Drug Abuse reported that nearly 5 million people 18 or older had used cocaine in the past year in the United States.31 The National Survey of Drug Use and Health reports that most cocaine users are between the ages of 18 to 25.32

Cocaine and Its Future in America

Cocaine in the United States has had a long, bumpy history, and still continues to be a dangerous drug of abuse. In 1993, the Journal of Clinical Pharmacology estimated that 25 percent of Americans—50 million people at the time—were using cocaine, with 6 million snorting or smoking it on a regular basis.33

Getting Help for Cocaine Addiction

Fortunately, there is effective treatment for individuals struggling with cocaine addiction, or other substance use disorders. If you or a loved one is ready to get on the road to recovery River Oaks Treatment Center is ready to help you get there. At our inpatient rehab near Tampa we offer an array of treatment services, including a safe and effective medical detox, to help people find meaningful recovery from substance use disorders.

Contact our helpful and compassionate admissions navigators at to learn more about our different levels of care or to start addiction treatment admissions. Our navigators can help you verify your rehab insurance coverage or give you information about how to pay for rehab.